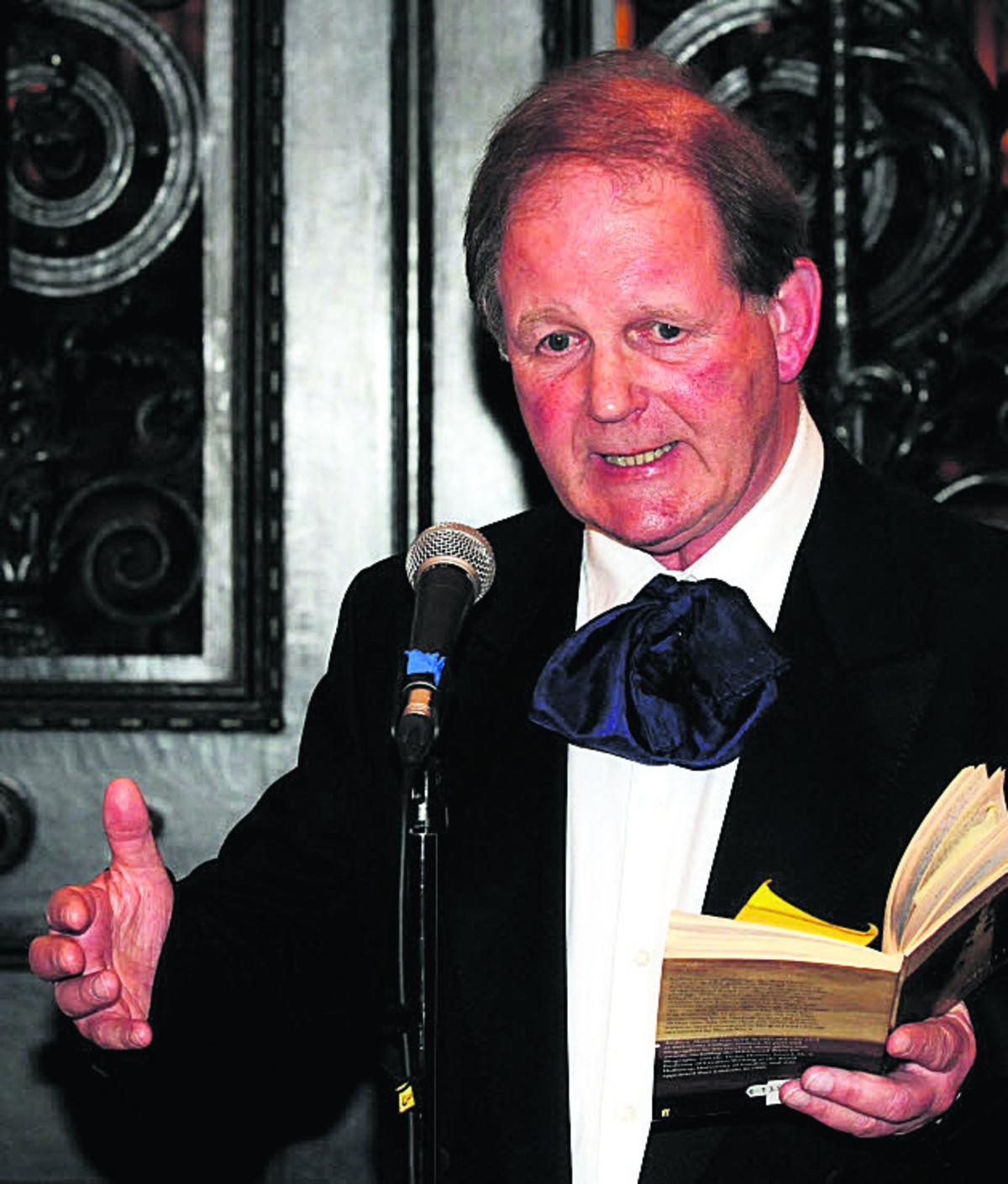

Former Children’s Laureate Michael Morpurgo revealed the inspiration behind his best-selling novel War Horse to guests at a charity dinner on Friday.

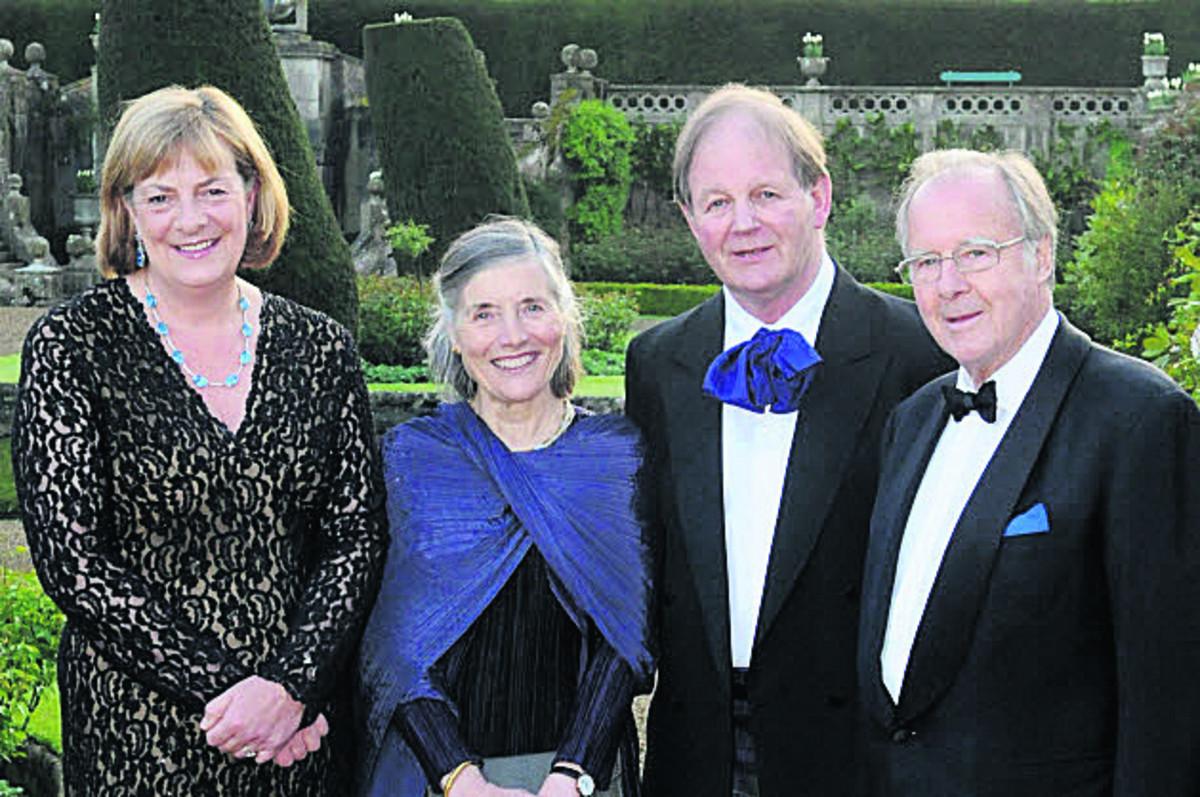

The dinner, at Lord and Lady Lansdowne’s home on the Bowood estate, near Calne, was held to fundraise for Morpurgo’s charity, set up with his wife Clare in 1976.

The charity, Farms for City Children, gives inner-city children an experience of rural life and was also the catalyst for the creation of War Horse.

War Horse, Morpurgo’s sixth book, has since been adapted into a play staged by the National Theatre and a film directed by Steven Spielberg.

Guests at the three-course dinner heard the story of a boy from Birmingham who stayed on one of the charity’s farms and built a special bond with a horse.

Morpurgo said this convinced him he could write War Horse, told from the point of view of Joey, a horse bought by the army for service in the First World War.

The 70-year-old, who entertained in Bowood’s ornate sculpture gallery and orangery, began his talk by commenting on the room’s wartime history. From 1915 to 1919 the orangery served as an auxiliary Red Cross hospital with 20 nurses looking after 54 convalescing patients.

As the country begins remembering the centenary of The First World War he also spoke of his own post-war upbringing, which has inspired several wartime novels.

Mr Morpurgo said: “I was a war baby, born in 1943. As I grew up, I soon learned how war had torn my world apart.

"I lived next to bombsites, and played in them with my friends because they made the best playgrounds imaginable and we weren’t supposed to.

“But I soon learned that much more than buildings was destroyed by war. My beloved uncle Pieter was killed in 1940, in the RAF, and I witnessed my mother’s grief which she lived every day. I missed him and I’d never really known him.

“All I knew was what I’d been told, that he’d given his life for our freedom. I thought the world of him for that. I still do.

"War continues to divide people, to change them forever, and I write about it both because I want people to understand the absolute futility of war, the ‘pity of war’ as Wilfred Owen called it.

“It’s so important to remember, to tell the story of soldiers who died, of those who witnessed the war on both sides, who lost loved ones – fathers, brothers, sons.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here