THE persecutions were already under way in Wiltshire when self-appointed Witchfinder General Matthew Hopkins’ initiated his reign of terror – the savage, full-scale victimisation of predominantly elderly, poor, illiterate, bent, bedraggled and beggarly women.

Around 300 unfortunates were executed in the East of England as a result of Hopkins’ dedicated work in tracking down, torturing, prosecuting and sending to the gallows aged, haggard members of the opposite sex during a brief, sadistic saga.

The crusader’s selfless services to a puritanical God fearing public, however, would not have been required in North Wiltshire during the mid-17th Century when his community spirited and highly profitable efforts were in full swing.

More than enough resentment, suspicion and prejudice permeated the country’s oldest borough to ensure that several Witches of Malmesbury paid the ultimate price for their perceived necromancy and devilment.

It is an episode that festered for three decades in Malmesbury before coming to a grisly conclusion on a scaffold in Salisbury in 1672.

Afterwards it was swiftly swept under the carpet, perhaps through shame or embarrassment as more enlightened times emerged and simply vanished from memory. Until now, that is.

The full story has finally been told by Wiltshire researcher/historian Tony McAleavy who uncovered dribs and drabs of the yarn over the years before throwing himself into the project to produce a 46-page booklet, The Witches of 17th Century Malmesbury.

He has shown that at least four local women died after being accused of witchcraft, while also conclusively proving that two of them swung as a result of Malmesbury Witch Trials.

His “largely untold story” begins during the Civil War in the 1640s when a woman called Alice Elgar was so “widely feared and despised as a witch” that she was set upon by the Malmesbury mob, and roughed-up so badly that she crawled home and “poysoned herselfe.”

Alice was described as “audaciously obnoxious” – which probably meant she begged with menaces.

Begging for yeast on the doorstep of a Malmesbury brewer in 1659, her friend Goody Orchard was turned away by ten year-old Mary Bartholomew… but not before uttering: “Then you will give me none? ‘twere better for you, you had.”

Immediately after leaving, her father Hugh Bartholomew’s wooden cash chest fell over and split. Clearly, it was the witch’s work.

Fleeing Malmesbury, Goody spent months cold and hungry on the road before begging for food in Burbage. Rebuffed by a 17 year-old girl, she “cast a spell” upon the teenager whose finger joints later became painful and distorted.

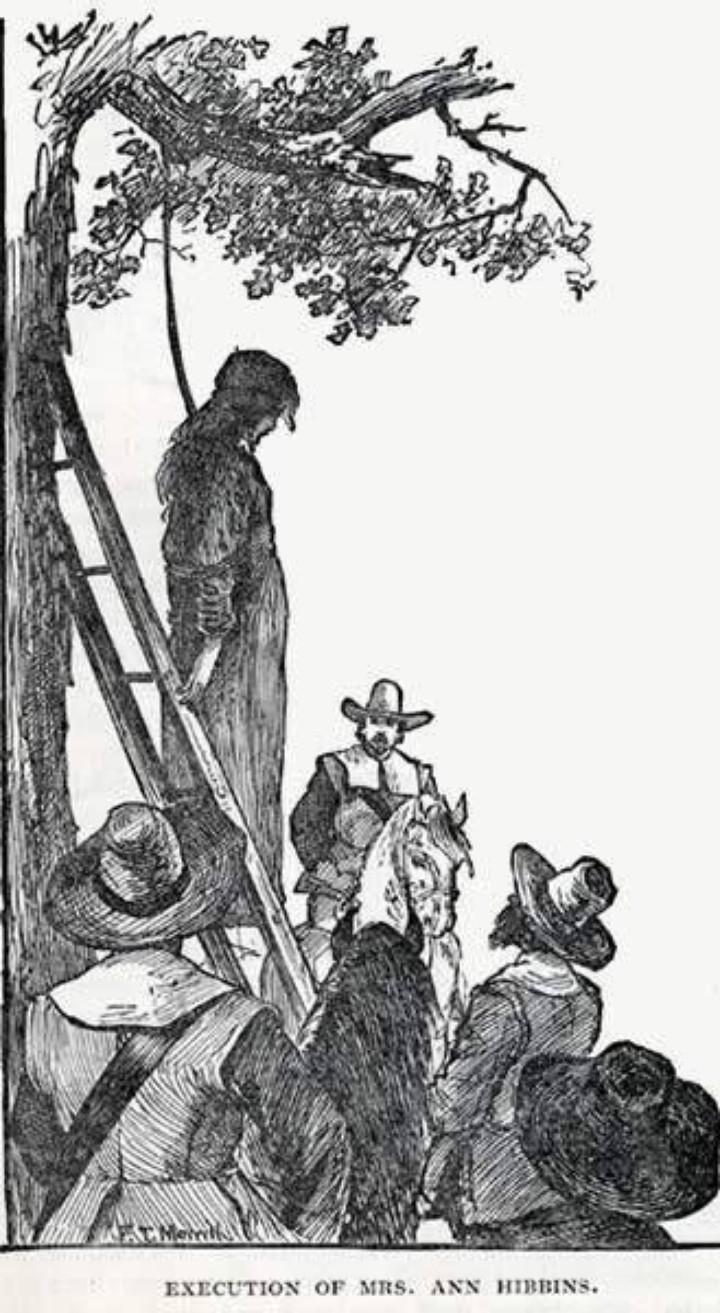

A hunt was swiftly mounted and the “witch” was nabbed three days later before being convicted and hanged at Salisbury – partly due to the testimony of Mary Bartholomew.

Over the years Mary became convinced that the other Witches of Malmesbury were “out to get her” in revenge for Goody’s execution – especially the alleged leader of the alleged coven, Elizabeth Peacock.

Becoming Mary Webb, the wife of a wealthy glover, she naturally blamed the local witches when her children fell ill. As a result Elizabeth was in 1670 tried for witchcraft - but to Mary’s horror she was acquitted.

A disturbing picture began to emerge, however, as seven prosperous, respected local families, led by the Webbs, got their heads together and laid the blame for virtually every illness that befell them on those evil witches.

Deaths from years gone by, disabilities, unexplained ailments – even their horses becoming lame. It was all the fault of some wrinkly, warty old women in league with the devil… the cursed Malmesbury Coven.

As McAleavy writes: “Old memories and suspicions were being dredged up in the heated atmosphere of 1672.”

Four grim-faced justices descended on Malmesbury including the eminent Sir James Long as 14 suspected witches and their accomplices were rounded up and severely grilled, probably during long periods in custody.

Long suggested that Malmesbury would hold itself to ridicule if 14 people were sent for trial “without solid evidence”. So they settled on four.

Eleven charges, ranging from “feloniously lameing Thomas Webb, Thomas Peters, Alice Webb and Margery Brown by witchcraft” and “murdering Margery Neale and Mary Sharp by witchcraft” to killing and laming assorted geldings and mares also by witchcraft were proffered.

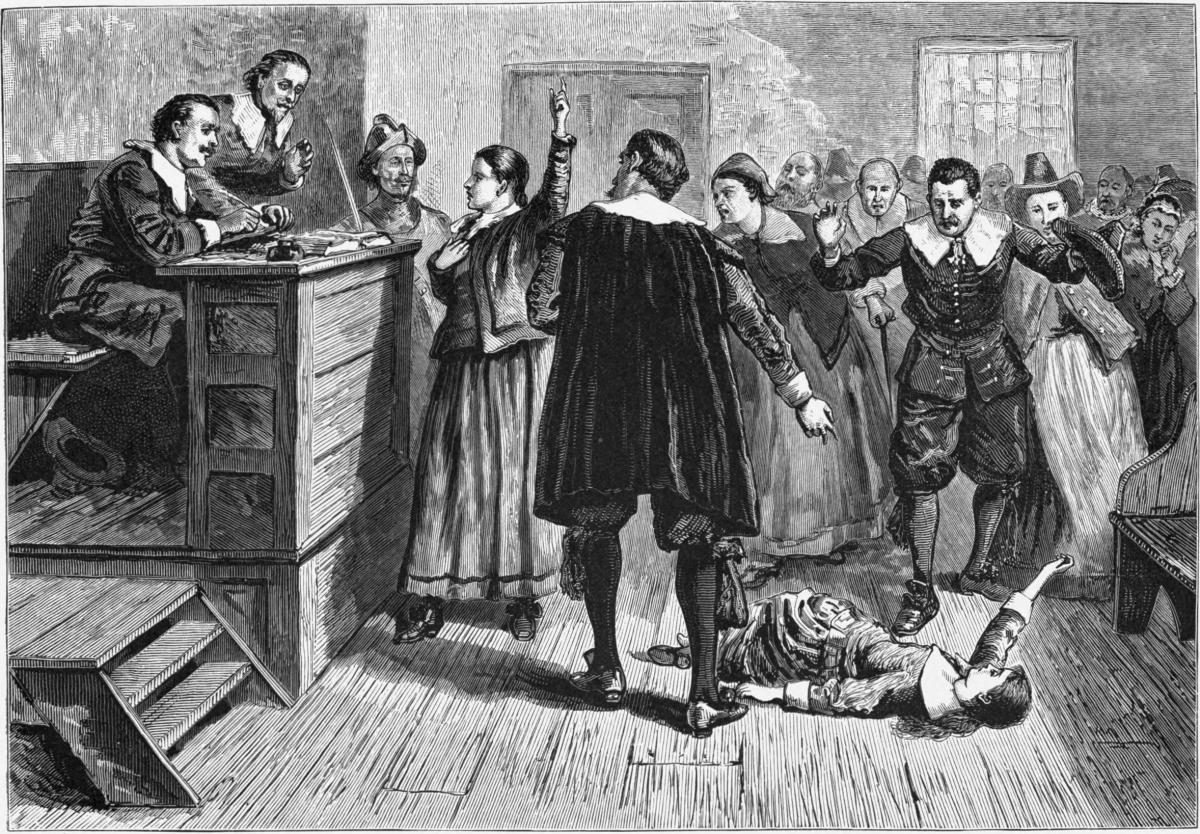

We can only imagine the furore in the public gallery at Salisbury Assizes among the enraged, witch obsessed folk of Malmesbury as they demanded the blood of Elizabeth Peacock, her sister Judith Witchell, Anna Tilling and Elizabeth Mills.

“We can be confident that the court was packed with the people of Malmesbury who demanded that the witches be hanged,” writes the author.

“Doubtless there was a particular clamour for the death of Elizabeth Peacock, the notorious leader of the Malmesbury Coven.”

No record of the evidence, alas, survives. However the court book reveals that Judith Witchell and Anna Tillage were found guilty while the coven’s hated leader Peacock was acquitted, as was Mills.

Tillage was officially proclaimed a witch after alleging that the local coven had invoked fits in young Thomas Webb “with the helpe of theyre spirits”.

A good friend of the Webbs, perhaps she testified against the others in the hapless hope of monetary gain. If so the ploy fatally backfired.

McAleavy is convinced Witchell could only have been found guilty after confessing - the days of dunking women into a river to determine whether they were witches or not appear to had passed.

It is likely that the illiterate defendant scrawled her mark to a confession after a long, arduous, mentally and physically punishing term in atrocious conditions at Salisbury Gaol.

Sir Richard Raynesford, one of the most prominent judges of his generation and “an undoubted believer in witchcraft”, pronounced the only sentence possible, as introduced by James I in 1604.

Tilling and Witchell were publically hanged at Salisbury – presumably amidst a tumult of jeers, howls and curses from baying spectators.

With a new age of reason and science on the horizon, they were among the last women ever executed for witchcraft in England.

- TWO key documents, along with hours delving in court and county records, helped Tony McAleavy piece together the story of The Witches of 17th Century Malmesbury.

Seventeenth Century writer John Aubrey wrote that “a cabal of witches” were detected in Malmesbury during the 1670s.

The Wiltshire antiquary somewhat fancifully declared that they were involved in “odd things” such as “flying in the aire on a staffe.”

He wrote that “seven or eight” of them were hanged.

Magistrate Sir James Long wrote a more considered account but it was not published until a gentleman’s magazine picked up the story 150 years later.

During his research McAleavy was thrilled to come across the will of “coven leader” Elizabeth Peacock in the Wiltshire Records Office.

Elizabeth, “who refused to confess,” had returned triumphantly to Malmesbury and lived for there for three years before being given a Christian burial in the Abbey churchyard.

McAleavy, 60, adds: “The story of the Malmesbury witches is one of great sadness. At least four elderly women from the town died miserable deaths.” - The Witches of 17th Century Malmesbury is published by Athelstan Museum (01666 829258) £5.

- WITCHRAFT, or the persecution of suspected witches, was rampant in Western Europe from the 15th to the mid-18th Century when some 200,000 were tortured, burnt or hanged.

They were mostly poor, elderly women with a ‘crone-like’ appearance, snaggle-toothed, with sunken cheeks or a hairy lip.

Others were said to have had “the devils mark” – a wart, mole, a birthmark, Even a flea-bite was deemed as proof.

Many were condemned simply on appearance and executed after appalling torture.

The ‘pilnie-winks’ (thumb screws) and iron ‘caspie-claws’ (leg irons heated over a brazier) usually wrung a confession.

Others were tied up and flung into a river. If she floated she was a witch. If she drowned she wasn’t. One such incident is said to have taken place on the Thames in Lechlade.

In August 1612, the Pendle Witch Trials in Lancashire saw ten people from three generations of one family hanged.

An unsuccessful lawyer called Matthew Hopkins (1620-1647) became England’s infamous Witchfinder General.

Between 1644 and 1647 he scoured the East for devil women and was paid handsomely to “clear towns of witches”.

He is said to have been responsible for the deaths of between 200 and 400 people, mostly elderly women.

Always value for money, he had 68 poor souls put to death in Bury St Edmunds alone, and 19 hanged at Chelmsford in a single day.

The last execution for witchcraft in England, 37 years after Hopkins’ death, was in 1684 when Alice Molland was hanged in Exeter.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here