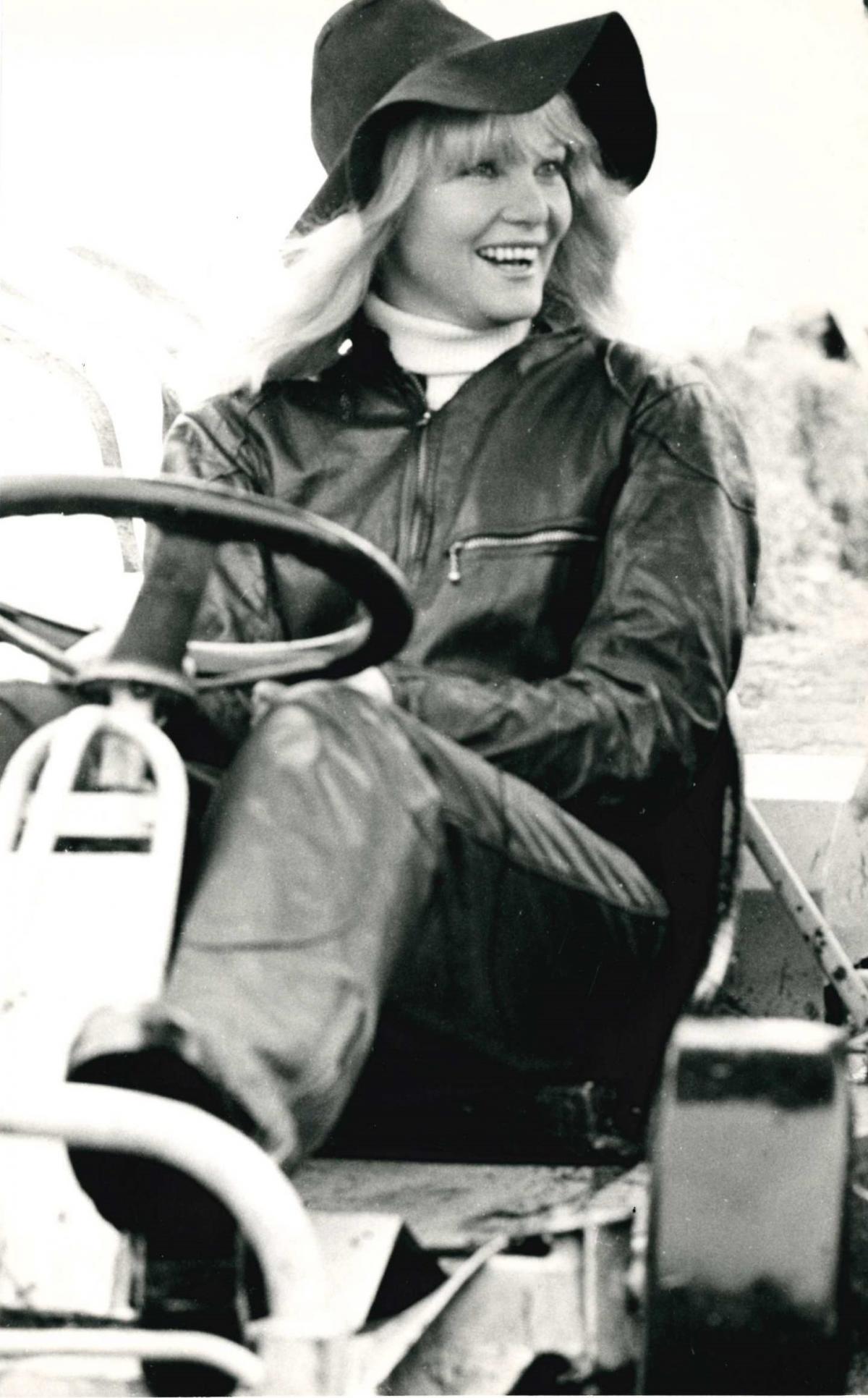

IN 1973 Diana Dors was easily the most famous Swindonian, just as she’d been for more than two decades.

It was hardly surprising that her home town newspaper covered every development in her career.

This week in the glam rock summer of that year, Diana made an appearance in Steptoe and Son Ride Again, the second celluloid spin-off from the beloved sitcom.

Shown countless times on TV since, it saw Albert and Harold acquire a racing greyhound and become involved with insurance fraud.

Although the actress’ character wasn’t even credited with a name, and appeared briefly as a woman Harold encountered on his rounds, Diana appeared alongside stars Harry H Corbett and Wilfrid Brambell on thousands of cinema posters.

The film was shown in Swindon at the ABC cinema in Regent Street, which is now the Savoy pub. Box office returns would be respectable, but our reviewer was less than impressed.

“It must be an admission of defeat by filmmakers that they are continually borrowing from their television rivals,” he wrote ahead of the opening.

“We’ve had cinema versions of On the Buses, Dad’s Army and Love Thy Neighbour (due in Swindon soon).

“Worse than that, filmmakers have now turned these transfers into long-running series.”

He needn’t have worried about the Steptoe and Son films becoming a series, as the plug was pulled after two.

Another star of the era made her home not far from Swindon, and was also mentioned often in the Adver.

This week in 1973 the news was sad: “Actress Diane Cilento, who lives at Scotts Farm, Pinkney, near Malmesbury, today confirmed that she and her husband, Sean Connery, were getting divorced.

“‘Yes, it is true,’ said Miss Cilento, when an Evening Advertiser reporter telephoned her at Scotts Farm following a statement made by her mother, Lady Cilento, in Australia, that divorce proceedings were pending.

“She decided to make no other comment.”

Diane moved to Australia some years later, and died there in 2011.

There are many other branches of showbusiness, and being a pub landlord is arguably one of them.

Roy West, mine host at The Crown in Aldbourne, certainly fit the bill when we visited for a feature on the ancient village.

We first explained that villagers were nicknamed dabchicks, supposedly because a dabchick - or little grebe - had landed on the village pond many years earlier and gone unidentified until the oldest man in the village was taken to the pond in a wheelbarrow and asked for his opinion.

“Several centuries later,” we said, “a few weeks ago, as a matter of fact, another bird landed on the village pond. This was a wounded mallard with an injured wing. This is fact, not legend.

“The mallard was taken by Roy West, licensee of The Crown, to a vet.

“After nearly passing out on the operating table, the mallard was fixed up with a steel pin in his injured wing - a drake, you see - and nursed back to health.

“‘We call him Quacker,’ said Mr West.

“Quacker was given a mate to play with, and now there is a family of ducklings at The Crown. Things like that seem to happen at Aldbourne.”

As famous Swindon people went, nature author Richard Jefferies’ profile was nowhere near as high as that of Diana Dors, not least because he’d been dead since 1887.

That hadn’t stopped his fame from spreading to the other side of the world, however.

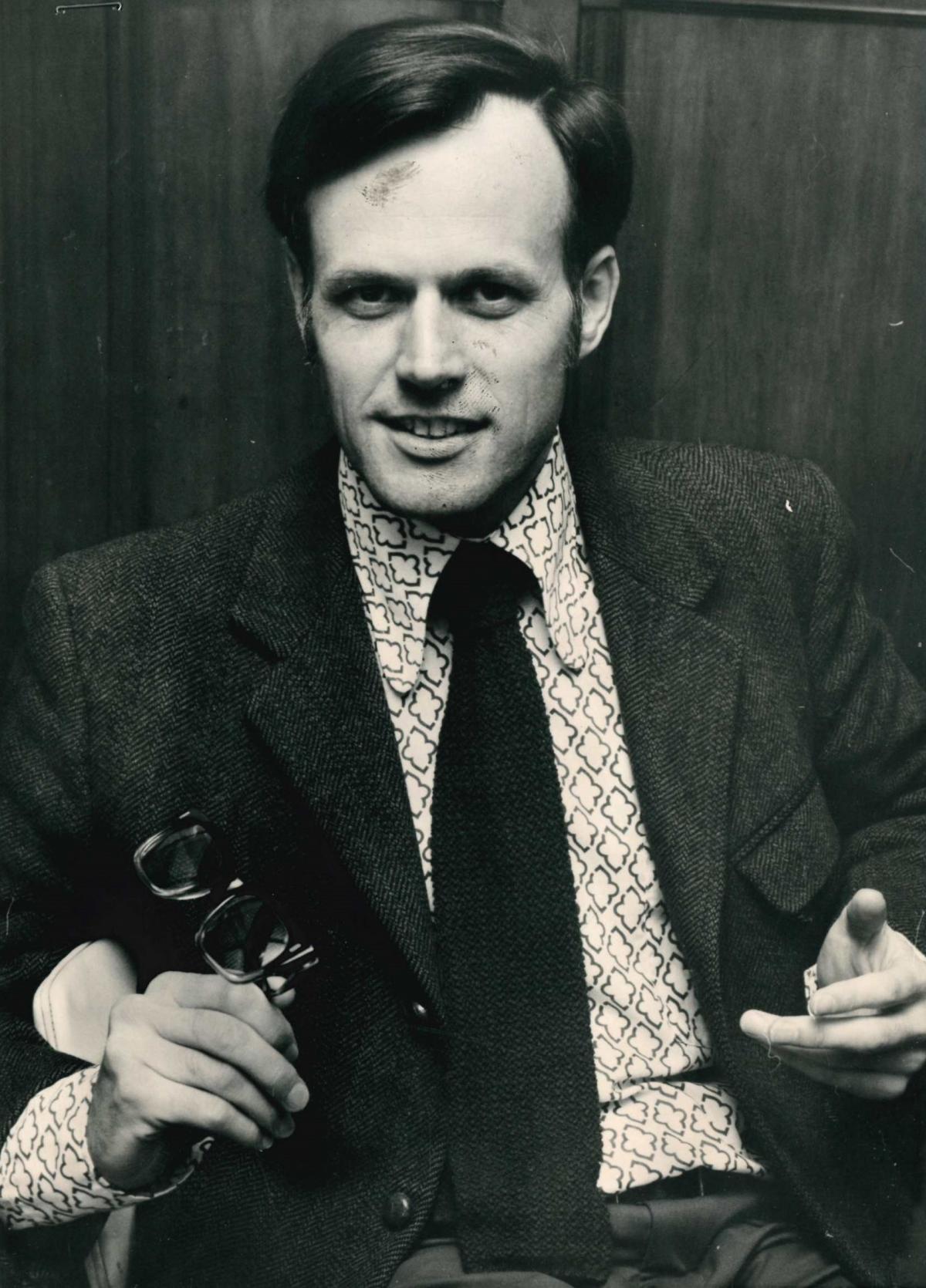

“A New Zealand lecturer,” we said, “has been in Swindon for the first time since his student days to study his favourite writer - Wiltshire author and naturalist Richard Jefferies.

“Mr Jeremy Commons, 39, is on a year’s leave from the Victoria University in Wellington, where he is a senior English lecturer.”

Mr Commons had been a devotee since the age of 14, when he discovered books brought over by his grandfather when he sailed from Falmouth.

“I was at a very impressionable age and I liked his work immediately, but it is extremely hard to find in New Zealand.”

In those days, more than two decades before the likes of Amazon began trading, adding to his collection was a matter of scouring bookshops during occasional trips to England.

The academic taught some of Jefferies’ works to his students.

“Initially they find his style rather gushing,” he said, “but when they tackle his thought they find it fascinating even though the plants and trees he wrote about are for the most part unknown in New Zealand.

“We tend to live such frantic and busy lives in concrete jungles that to find somebody who loved walking and nature comes to students as a very healthy and pleasant surprise.”

Jeremy Commons went on to become a respected opera historian.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here