JOE Keampfer gazed at the robust redbrick surroundings and declared with an air of excitement tinged with the brutal honesty of a hardened businessman: “These are not the most beautiful industrial buildings. But more trains were built here than anywhere else in the world.”

The man whose passion for railways began during family outings back home in Connecticut when his dad dragged them along to gape at locos and turntables, continued: “It’s got great character. I love this. It’s better than any office I have at home.”

Warming to the theme, Washington-based father-of-two Joe, 49, further enthused: “This was a catalyst in the industrial revolution. It’s quite amazing when you think how many thousands of people used to work here making engines.”

The place is festooned with cranes, gantries, presses, columns and other intriguing heavy metal relics from a vanished industrial age all gleaming in their fragrant coats of newly-applied paint.

Many resemble striking works of modern sculpture that remain in situ as a lasting tribute to their functions from a distant era.

One particular crane having suddenly caught his eye, Joe grinned as if imagining the implement swinging noisily into action more than a century earlier.

“This was an era before Henry Ford invented the assembly line,” he was keen to point out. “They picked up 40-ton engines with giant cranes and moved them around.”

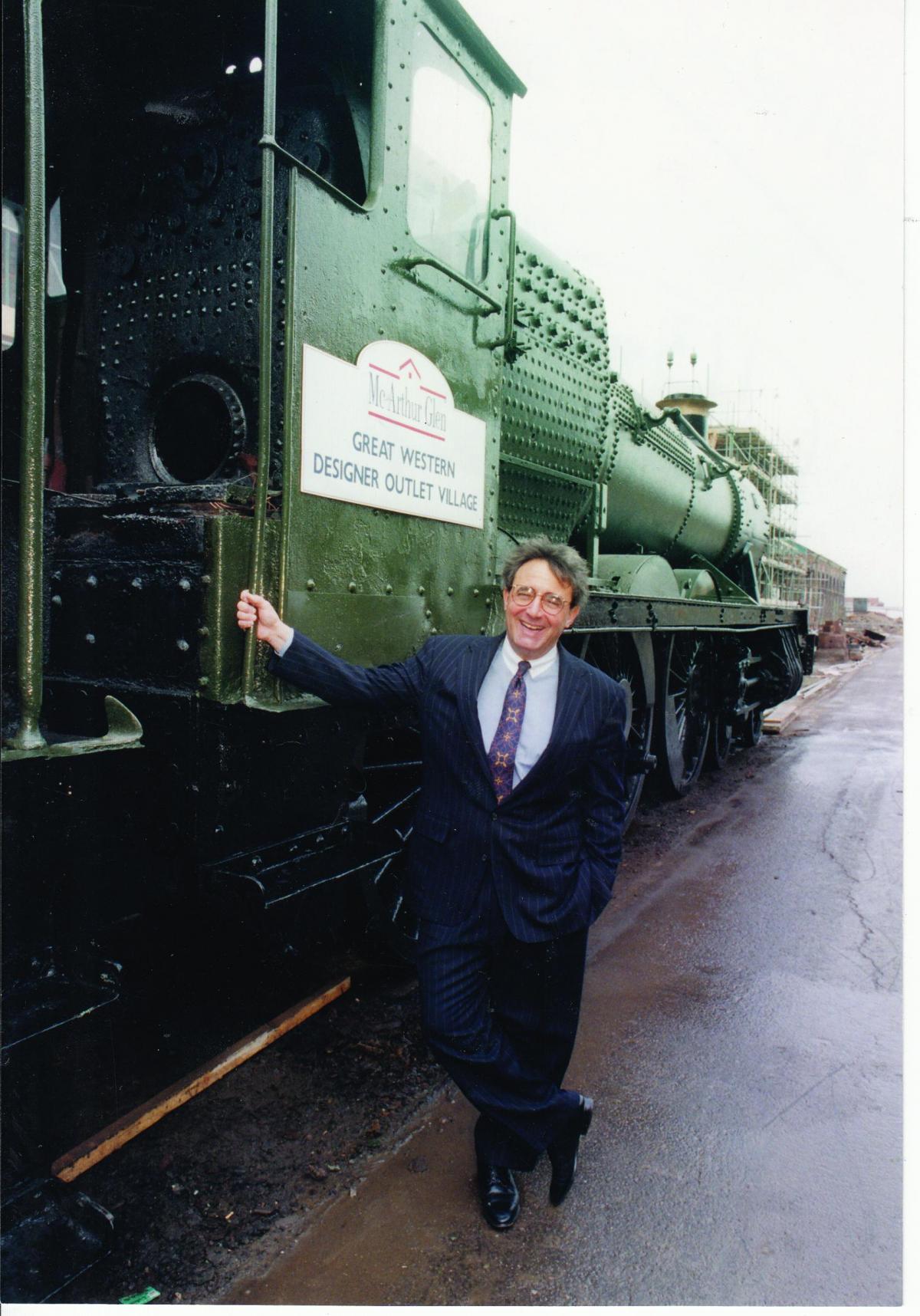

It is March, 1997 and Joe Keampfer, Chief Executive of BAA McArthur/Glen is strolling through his company’s new domain…some huge former engineering shops at the old Swindon Railway Works which, for the first time in a decade, have been buzzing with activity.

It is just over a week before the grand opening of the Great Western Designer Outlet Village – which is what it was called then – that signalled the re-birth of a sizeable chunk of the Swindon Works into “the most dynamic new retail venue in the UK.”

Nearly 100 boutique style units have been stylishly fashioned in steel and glass within this cavernous, sturdy complex in a £40 million project that has seen derelict 19th Century engineering shops transformed into stylish late 20th Century shops of a different kind.

Some of the airy malls with their exposed original brickwork, in which I am wandering with Joe and a few other Important American Visitors, date to 1842… the very infancy of both the GWR Works and the Town of Swindon as we know it today.

Emerging from a time machine, would Mr Brunel recognise in its pristine new guise the original GWR smithy that he almost certainly designed during the early years of Queen Victoria’s reign? Maybe.

A man of vision, however, he would undoubtedly have appreciated the ethos of converting something old and redundant into something new and of worth and relevance.

I am reminded of the Reawakening of the Railway Works 18 years ago because Swindon Designer Outlet – which is what it is called now – has been shortlisted for a conservation award after its £35 million expansion into the Long Shop.

The complex has scooped a bundle of awards for its treatment of The Works over the years.

However, these structures from the Dawn of the Railway Age where people today shop for designer clothes and fancy chocolates were once in real danger of being flattened to make way for just another Swindon housing estate.

During the late Seventies/early Eighties the closure of the Swindon Works after almost 150 years was inevitable.

Accountants at British Rail Engineering Ltd were presumably dribbling in anticipation of a fat juicy sum for 325 acres of prime development land in Britain’s fastest growing town.

But they were partially thwarted when 11 ex-GWR structures achieved listed status while the council declared the site’s 52-acre core a Conservation Area – thus restricting its future use and preserving a vital slice of Swindon’s heritage.

This may seem an obvious ploy today but back then attitudes were different and Britain’s industrial buildings were tumbling like cards.

Visiting the Swindon Works in 1999 the Prince of Wales was moved to proclaim: “For the last 35 years I have watched in despair as one remarkable industrial building after another has been systematically demolished – mercilessly swept away in a fashionable frenzy.”

No-one would listen to “a few brave souls,” he said, who begged developers to convert rather than demolish such structures.

Citing the revitalisation of the Swindon Works he said: “Now at long last and before the dwindling number of our unique heritage buildings are finally expunged from our townscape it seems common sense has begun to reappear – albeit hesitantly.”

Tarmac acquired the Swindon site, and as far back as 1989 – three years after The Works finally ground to a halt – rumours of a Covent Garden-style regeneration were in the air.

Also, the words “factory shops” suddenly entered the Swindon vocabulary.

Ten years after it was abandoned to the elements and the pigeons I was among a group press people ushered around the dank, derelict, dropping-encrusted sheds in 1996.

Cracked and shattered windows, rusty, abandoned machinery, puddles of water from leaky roofs — it was cold, unwelcoming and – for those with an imagination — haunted by the ghosts of tens of thousands of hammering, welding, cursing railwaymen.

Weeks later the aforementioned ironsmith’s shop, one of the first structures built at the Works in 1842, and the boiler and tank shops from the 1870s, were being resuscitated.

Swindon’s redbrick revival was truly on the march as 650 workmen brought 200,000 sq. ft. of Victorian factory floor back into use.

And – nice touch, this — they left decades of soot ingrained between the bricks to help maintain its Victorian character and atmosphere. It was certainly cheaper than removing it.

Sir Neil Cossons – a humble Swindon museum employee who had risen to the dizzy heights of Chairman of English Heritage —put it this way: “McArthur Glen’s bold and imaginative scheme respected and retained the original structure and architecture.

“It applied, as The Prince of Wales remarked ‘a successful retail formula developed in the shopping malls of the New World to one of the most important heritage industrial buildings in the Old.’”

You may have no time for Karl Lagerfield watches while Belega handbags might not be your bag. You may even find the scent of Yankee Candles nauseating. But you have to tip your hat – trendy designer brand or not — to Swindon’s most important regeneration project.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel